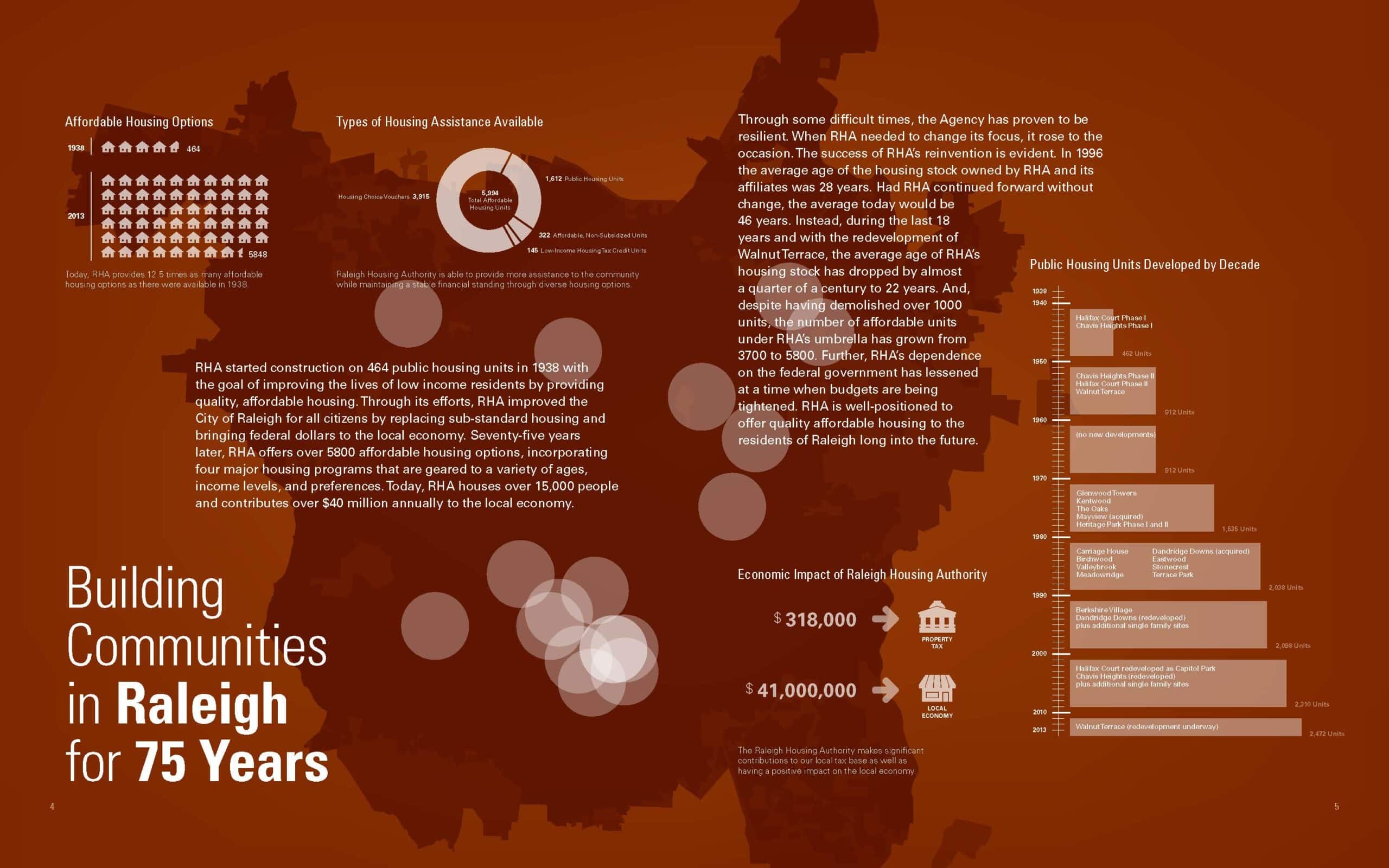

RHA started construction on 464 public housing units in 1938 with the goal of improving the lives of low-income residents by providing safe, quality, affordable housing. Through its efforts, RHA improved the City of Raleigh for all citizens by replacing the sub-standard housing and bringing federal dollars to the local economy. 75 years later, RHA offers over 5,800 affordable housing units, incorporating four major housing programs that are geared to a variety of ages, income levels and preferences. Today, RHA provides housing assistance to more than 11,000 people and contributes in excess of $55 million annually to the local economy.

A Message from Our CEO,

Ashley Lommers-Johnson

Ashley Lommers-Johnson began his tenure with RHA in April 2023 after serving over 10 years as the Executive Director of the Housing Authority of the City of Everett, Washington. Before coming to Everett, Ashley served approximately 7 years as the Associate Deputy Executive Director, Housing Operations, with the Housing Authority of Baltimore City.

Mr. Lommers-Johnson plans to continue RHA’s long history of operational excellence and growing RHA’s housing portfolio, while strengthening resident and community relations and building community partnerships. In addition to his commitment to these important focus areas, he believes strongly that developing a strategic plan that provides clear direction is vital for organizational health and growth.

Ashley’s strategic focus helped him become a leader in affordable housing preservation, acquisition, repositioning, and development. None of these achievements would have been possible without dedicated housing professionals motivated to serve those in need of high-quality affordable housing. Ashley is a strong proponent of robust training, professional development and the opportunity for meaningful work as essential ingredients of long-term personal and organizational growth. He is confident that RHA will become a magnet for talented professionals who want to make a difference.

“As much as I have valued the opportunity to lead the Everett Housing Authority, I am excited to inspire an organization with a history of operational excellence to even greater heights. I look forward to collaborating with RHA’s residents and community partners to take on the challenge of expanding Raleigh’s affordable housing options during this time of exceptional growth and economic opportunity.”-Ashley Lommers-Johnson

Ashley grew up in Cape Town, South Africa, where he received a Bachelor of Arts Degree from the University of Cape Town. He also holds a Master of Arts Degree in Linguistics from Northwestern University and a Master of Public Affairs from the University of Washington’s Evans School of Public Affairs.

Housing in Raleigh before the Raleigh Housing Authority

In the late 1930s America was still trying to free itself from the Great Depression. Unemployment was over 20% and families were struggling to make ends meet, many of them in unsafe and unsanitary housing. Working people were in low-wage jobs or only able to secure sporadic employment. There was very little vacant housing in the City of Raleigh. The need for housing was great.

In Raleigh there were pockets of slum housing that by any standard would be considered unsafe and unsanitary. Houses were located very close together with wood or coal as the primary sources of heat. This raised concerns relating to fire and the probability that it could spread quickly from one home to others. Homes had little insulation and many homes did not have electricity.

Many of the initiatives that started during the Great Depression focused on homeowners with little attention directed toward families in need of rental housing. Toward the end of the 1930s and early 1940s, the nation’s attention began to move toward housing rental families and addressing the stubbornly high unemployment. “Slum clearance” was viewed as a way of adding local jobs while also addressing the need for housing. The high level of substandard housing started to receive more attention as citizens began to believe that our nation could not be great with so many of its residents living in squalor. In a News and Observer editorial from 1939 it was stated, “A decently housed citizenship is the first essential to a good citizenship. Better housing means a better town.” This sentiment represented the thoughts of many Raleigh residents.

What is a housing authority and how is it funded?

Meeting Housing Needs:

1938 to 1969

After much discussion, Congress passed the U.S. Housing Act of 1937 which was the first national housing legislation. This legislation served a dual purpose: providing low-cost housing to replace slum housing and improving the lagging economy by providing jobs in the building industry. This Act established the United States Housing Authority and provided for the establishment, through state law, of local public housing authorities to build, own, and operate housing for low-income families.

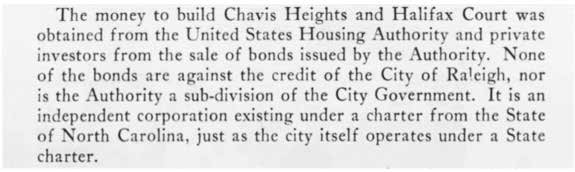

Housing authorities are chartered by the state and are not part of city government. Any locality that wished to form a public housing authority had to secure approval from the city commissioners and raise a certain amount of local funding (10%) to match with federal funding for the construction of public housing. Raleigh was the second municipality in North Carolina to reach its fundraising goals, and the RHA was founded in 1938. With the funding in place, plans began for the purchase of land for construction of two public housing sites – Halifax Court for white families and Chavis Heights for black families.

Each locality established its rents taking into consideration the incomes and sizes of the families to be served. In the segregated society, the rental rates for minorities were lower than for white families because their incomes were less. The authority funded its operations from the rents it collected. By the start of 1942, RHA had constructed and occupied 464 units on the two properties. The authority added 150 more units to these sites in 1952 to address the needs for veterans’ housing. RHA completed a third large site in 1959 called Walnut Terrace.

After much discussion, Congress passed the U.S. Housing Act of 1937 which was the first national housing legislation. This legislation served a dual purpose: providing low-cost housing to replace slum housing and improving the lagging economy by providing jobs in the building industry. This Act established the United States Housing Authority and provided for the establishment, through state law, of local public housing authorities to build, own, and operate housing for low-income families.

Housing authorities are chartered by the state and are not part of city government. Any locality that wished to form a public housing authority had to secure approval from the city commissioners and raise a certain amount of local funding (10%) to match with federal funding for the construction of public housing. Raleigh was the second municipality in North Carolina to reach its fundraising goals, and the RHA was founded in 1938. With the funding in place, plans began for the purchase of land for construction of two public housing sites – Halifax Court for white families and Chavis Heights for black families.

Each locality established its rents taking into consideration the incomes and sizes of the families to be served. In the segregated society, the rental rates for minorities were lower than for white families because their incomes were less. The authority funded its operations from the rents it collected. By the start of 1942, RHA had constructed and occupied 464 units on the two properties. The authority added 150 more units to these sites in 1952 to address the needs for veterans’ housing. RHA completed a third large site in 1959 called Walnut Terrace.

In the early years of public housing very strict tenant selection policies were in place. Unwed pregnant women could be evicted and large fines were levied for property damages. A staff member would visit the home of each applicant before they were considered for public housing occupancy. Families were required to have two parents in the household, employment, good personal references, and live in substandard housing. During these years, RHA functioned as a business with minimal regulations and funding from the federal level. Public housing was functioning as intended – families moved in, stabilized themselves, and moved out for other housing opportunities. However, this changed drastically in 1969.

In 1969 the Brooke Amendment was added to the Housing Act of 1937 which would forever change the way public housing was funded and operated.

This amendment set the maximum rent an assisted family would pay at 25% (and later 30%) of family income. Prior to this time, housing authorities had been increasing rental rates to cover increasing costs. In order to limit the rent that could be collected, the federal government added operating subsidies to cover the expenses that the limited rents did not. Along with this federal funding came increased regulation which continues today.

A Time of Growth and Change: 1970 to 1995

Another significant development in 1974 was the implementation of the “Section 8” tenant-based rental assistance program, currently known as the Housing Choice Voucher Program and RHA’s largest housing program. Unlike the public housing program, the voucher program matches participants with landlords in the private sector. Participants pay 30% of their income for rent and the housing authority pays the balance to the private landlord. Another legislative action that greatly impacted operations was the passage of federal selection preferences. Agencies were required to give a preference to homeless applicants, persons living in substandard housing, and persons paying more than 50% of their income for rent.

By this time, the unintended consequences of the Brooke Amendment and the required preferences were taking effect. Public housing had become concentrated with extremely low income families who had a pressing need for supportive services such as child care, job training, and education to break the cycle of poverty. Sadly, providing these services siphoned resources away from the core mission of providing quality housing. This became tragically apparent in 1992 when two residents died in their Walnut Terrace apartment from carbon monoxide poisoning. As a result of this tragedy, RHA would undergo a complete reorganization and transformation.

The Agency would begin to seek partnerships with local service providers to secure services so staff could focus on RHA’s primary mission of providing safe, affordable housing. RHA began to explore options for upgrading units, and in some cases, the demolition and replacement of obsolete public housing units.

Mr. Craven Avery

Family moved into Walnut Terrace in 1969 when he was 13. He is also chairperson of the Walnut Terrace Reunion Committee.

The Inter-Community Council (“ICC”)

In 1971, a Chavis Heights resident named Mrs. Jessie H. Copeland had a vision of improving the interaction between residents and the Housing Authority. Her idea was to form an organization that would advocate for residents and improve communication between RHA and the residents. One of the first steps was to recruit and train resident leaders from each public housing complex to articulate the needs of the low-income families. Once this core group of leaders was in place, Mrs. Copeland’s vision expanded to a tax-exempt organization that could speak for all public housing residents in the city. The group was incorporated by the state as a 501(c)3 non-profit. The organization was originally known as the Inter-Project Council, Inc. However, the term “project” conjured up negative images and Mrs. Copeland came to detest the use of the term “project” to describe public housing communities. She insisted that the name be changed. In early 1990 the organization changed its name to the Inter-Community Council, Inc. (“ICC”) which it retains today.

There have been numerous leaders of the ICC. Two of the longest serving leaders are Mrs. Jessie Copeland and Ms. Lottie Moore. Mrs. Copeland brought the organization from infancy to maturity in her 30 years of involvement. She was known as the Mayor of Chavis Heights due to her unending efforts to improve public housing with a focus on Chavis Heights. She focused on education and The Inter-Community Council (“ICC”) believed it to be the one thing that could move a child or family out of poverty. In that regard she was instrumental in getting the City of Raleigh and RHA to work together to address crime and poor academic performance of public housing students. She was able to get Shaw University and St. Augustine’s College to provide scholarships to public housing children who graduated high school. Once she realized that few public housing children were graduating, her focus shifted to after-school and stay in school programs and later to providing scholarships. Over the years, these programs have evolved and have been absorbed into another non-profit, Communities in Schools of Wake County, which continues to provide after-school programs, free of charge, in five public housing communities.

Mrs. Copeland groomed a young working mother from Chavis Heights to become a resident leader. Ms. Lottie Moore relocated from Chavis Heights to the Oaks where she became the Resident President. Eventually Ms. Moore became the Chairperson of the ICC and she continued to serve in that capacity until her passing in 2023.

Today, the ICC continues to seek community partnerships that enhance the quality of life for residents. This includes programs related to job training, improving curb appeal, promoting healthy lifestyles, and spiritual programs. Ms. Jackie Williams currently services as the ICC Chairperson and Resident President for Glenwood Towers.

If you are interested in where you live, you will participate and take part to make it better.

Creating Vibrant, Diverse Communities: 1996 to 2015

The Agency decided to divest itself of programs that were not cost effective to operate so it could focus on its core mission and core programs. This freed up resources for RHA to improve its housing, get on solid financial footing, and to diversify its portfolio and income streams.

Programs from 7 to 400 units were shifted to other agencies or phased out, and from that point forward, RHA applied only for grants that were consistent with its core mission and would be cost effective to run. Quality became more important than quantity.

Before seeking to replace the units lost by these changes, RHA’s internal motto became “fix ourselves first.” The Section 8 program, which historically had lease-up rates between 84 and 88 percent, achieved 100 percent occupancy where it has remained since. RHA improved its inspection process to hold private landlords accountable and increased its fraud detection efforts to ensure accountability by program participants.

The public housing program, which had over 200 vacancies at the beginning of this period, went from less than 90% occupancy to 99% where it has remained during the ensuing years. In addition to improving occupancy, RHA improved the quality of its housing with a management by objectives approach. Solid maintenance and property management became the primary focus. Improvements in lease-up, rent collection, fraud detection, and inventory management generated funds which could be directed back into the properties. As sufficient funds became available, RHA became the first large housing authority in NC to add air conditioning to all of its public housing stock.

As additional resources were developed, RHA started to look toward improving its portfolio through replacement. A highly competitive new federal program titled HOPE VI permitted the previously unthinkable — demolition of outdated and dilapidated public housing and the ability for housing authorities to incentivize working residents. RHA had an excellent candidate for this program in Dandridge Downs. Shaw University constructed the complex as married student apartments in 1972. RHA bowed to pressure from HUD and took over the complex in 1977 using a process known as a deed in lieu of foreclosure, with only $2000 per unit to fix and modernize them. By 1994, RHA had vacated and boarded the property and sought redevelopment alternatives. RHA pursued numerous alternatives and ultimately achieved success when it received its first HOPE VI demolition-only grant in 1998, $500,000 to demolish Dandridge Downs. This was the first major step in dealing with its older properties. There was no federal funding to rebuild the complex so RHA completed the demolition, reactivated its dormant non-profit, and used it to construct 33 single-family homes on the site which it sold on the private market.

This multiple award-winning new community served as a catalyst in the surrounding community by igniting construction of market-rate homes, restaurants, retail, and a new dormitory for Peace College on land purchased from RHA. In 2003, RHA leveraged this successful new community completed on budget and in national-record time to secure a second HOPE VI grant – this time for the aging Chavis Heights. The new community went from full occupancy to full reoccupancy in three years and three months, a new national record.

With two of RHA’s three large, barracks-style developments now replaced by thriving new communities, the Agency set its sights on the last of the “big 3” properties – Walnut Terrace. By 2009, funding for the HOPE VI program had been cut to the point where only a few grants were awarded nationally each year and the end of the program was in sight. In December of 2009, the RHA Board voted to redevelop Walnut Terrace with or without a HOPE VI grant. This would be the largest development project ever undertaken by RHA and it would be accomplished without additional HUD grants or tax credits. The residents were relocated during 2010 and demolition was completed in 2011. Construction is underway and on schedule to be completed in 2014. Like both Halifax Court and Chavis Heights before it, the new Walnut Terrace will incorporate a mix of public housing owned by RHA and affordable market-rate housing owned by CAD, Inc. In addition, the new development will feature a park, community center, and a maintenance facility.

Throughout the nation, more than 3000 local housing authorities strive to improve the living conditions in their communities. Today, RHA is among the leaders setting the standard for quality affordable housing. It is a standard of which North Carolina’s Capital City can be proud.

Strategic Planning and Future Developments: 2015 to the present

Throughout the nation, more than 3000 local housing authorities strive to improve the living conditions in their communities. Today, RHA is among the leaders setting the standard for quality affordable housing. It is a standard of which North Carolina’s Capital City can be proud. Under its current Board of Commissioners and CEO, Raleigh Housing Authority is taking strides to update its aging housing stock while remaining a primary affordable housing provider.

Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD)

In 2019, Raleigh Housing Authority started to seek conversion of its public housing communities to the Section 8 program through the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program. RAD offers greater flexibility to ensure the preservation of RHA’s affordable housing, the ability to leverage new resources to address capital needs, and provides a more stable and reliable funding source in the face of continued federal cutbacks to the public housing program. To date, four communities have successfully converted: Berkshire Village, Terrace Park, Meadow Ridge and Valleybrook.

RHA’s goal with RAD is to ensure the long-term preservation of affordable, quality housing for current and future residents. Converted residents continue to receive housing assistance following conversion provided they continue to remain in good standing with their lease obligations. RHA maintains substantially the same operational rules, rent structure and resident rights that are in place now. Residents should feel very little day-to-day impact.

Heritage Park

The Raleigh Housing Authority owns and manages the Heritage Park community located in downtown Raleigh. Sitting on 11.61 acres of land, Heritage Park is made up of 122 residential apartments which were built in the 1970s. The buildings at Heritage Park are outdated and costly to maintain. RHA has the opportunity to rebuild this community to better serve low- to moderate-income families with new energy efficient, more spacious and modern apartments.

RHA is redeveloping Heritage Park in a way that will most benefit its residents while making a positive contribution to the citywide need for more affordable housing. Redevelopment planning takes time and careful consideration, and RHA has worked diligently on a plan that will benefit all who are directly impacted. RHA will be seeking increased density, enabling RHA to build more units on this property. Building more units equals more affordable housing choices for Raleigh residents. HUD approved RHA’s Section 18 application for redevelopment in December 2024. This project will be on-going for the next several years.

RHA’s Strategic Plan

Raleigh Housing Authority’s 2024 Strategic Plan lays out the organization’s strategy for improving the lives of employees and our customers, increasing affordable housing development, and reaching our goals for equitable, inclusive communities. The five strategic goals put forth in the plan present our vision of what RHA hopes to accomplish, our objectives for how we will reach those goals, and the strategies for achieving success.

The first goal is Vibrant Communities. RHA will create access to and develop vibrant, economically diverse communities of high opportunity throughout our jurisdiction. We will accomplish this through acquiring the necessary financial tools, such as an investment-grade credit rating, repositioning all housing developments to replace existing and add at least 2,000 units, preserving affordable housing with expiring affordability terms and expanding our housing stock with new construction opportunities. RHA also will better utilize the Housing Choice Voucher Program to create greater access to communities of higher opportunity.

The second goal is Thriving Customers. RHA residents and participants will live in communities where they and their households can thrive. We will accomplish this by planning, designing, and implementing programs, policies and services that focus on our customers. We will ensure high-quality interactions with staff and residents through ongoing trainings, measuring performance, and coaching efforts. RHA will leverage community services available to provide assistance and support for our customers to thrive.

Goal three is Organizational Health. We will continually maximize RHA’s Organizational Health to ensure RHA’s ability to thrive through challenges. By creating and following a strategic plan, we will increase employee engagement, satisfaction and create an environment for competitive compensation and benefits. RHA will use technology and new information systems to increase efficiency, effectiveness, and development, helping both existing and potential employees to do their best.

Strategic Goal 4 is Effective Partnerships. RHA will pursue effective partnerships with a broad range of mission-aligned organizations, establishing our brand, shared values, and communications goals. We will leverage community-based service providers to enhance the relationships between partners and customers for the benefit of both parties. RHA also seeks to build strong relationships with elected officials, City and County staff, nonprofits, and other housing developers to maximize partnerships and the availability of affordable housing.

The fifth goal is Racial and Social Equity. We will pursue and promote racial and social equity in RHA’s housing, community, and economic development efforts. Of primary importance is to address the disproportionate impacts of gentrification and displacement on Black and Hispanic communities. We seek to provide equitable access to living wage jobs through internships, entry-level positions with our partners, and leveraging opportunities for people of color. RHA will reach out to minority-owned businesses as part of our procurement practices and increase these strategic partnerships to provide opportunities for these businesses to grow and thrive